The grey tree frog featured last Thursday, Hyla versicolor, does indeed prove its versatility by changing its coloration depending upon factors including weather conditions and habitat. The mottled grey-green back of the individual caught near the pond is undoubtedly superbly adapted to life in the trees on Salt Pond Mountain; finding a tree (or, for that matter, a rock or a log) near the station not covered in lichen is a near impossibility. Worldwide, 14,000 known species of lichen thrive in habitats from artic poles and mountaintops to tropics to the backs of tortoises (a few species grow exclusively on the shells of barnacles that live in intertidal zones on the coasts of North America). However, both the fungal and the algal components thrive in cool, moist conditions like those found in many parts of the Appalachians.

A lichen is not an organism per se, but rather a term for an type of association between two wholly different organisms that has proved tremendously successful. The fungal cells involved in the formation of lichen typically belong to diverse species in the Ascomycota, a phylum of fungi distinguished by the tiny sacs which function as their spore-production units. Of the 30,000 species of ascomycetes, nearly half form lichen. These species are drawn from 13 major orders and do not share any special taxonomic relationship—they are only connected by the photosynthetic association they form.

All lichens are named and distinguished from each other according to the species of fungus involved. However, each lichen also involves a photosynthetic symbiont (shortened to photobiont) as a partner. Photobionts can be algae of various kinds, as well as cyanobacteria (which, though often called blue-green algae, are placed within an entirely different domain). The species of algal symbiont has been identified in only 2-3% of all lichens—and it may not be static within the same lichen. A few lichens have been shown to associate with both green alga and cyanobacteria (although not simultaneously). Others entertain different photobionts in different parts of their range.

Lichen species have traditionally been viewed as symbiotic relationships benefitting both fungus and photobiont—the photobiont receives structure, moisture, and protection while the fungus harvests photosynthetic energy for growth and spore production. A more recent take on the relationship is best described as a “controlled parasitism” of the photobiont by the fungus—while the fungus harvests energy produced by the photobiont, it must allow the photobiont to grow and reproduce in order to do so itself. But where are the boundary lines for “lichens” drawn? Do certain seaweeds consistently found with fungal infections, or certain mushrooms always found covered in algae constitute lichens? Without a clear definition of the fungal-photobiont relationship, “lichen” is a convenient classification only.

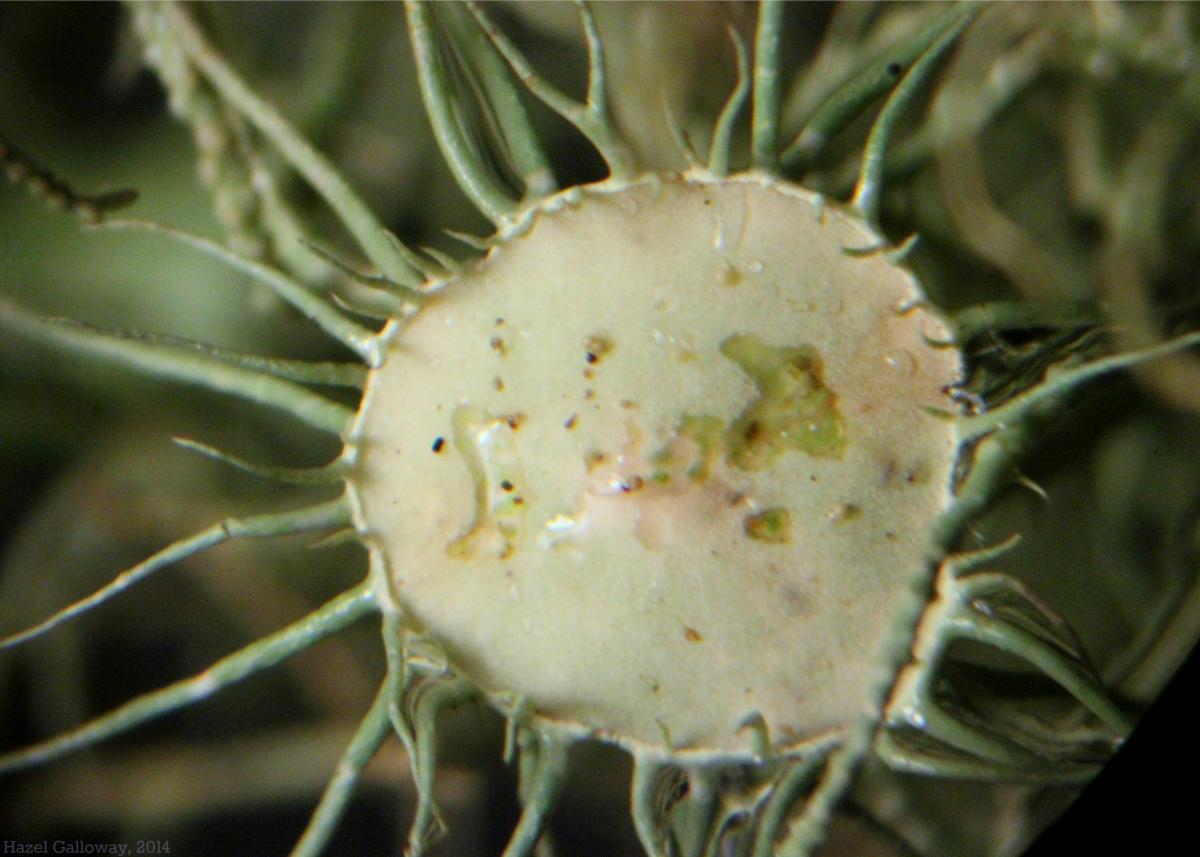

The genus Usnea is composed of shrubby or hanging, filamentous lichens usually grey-green in color. They derive the green from their photobiont algae, thought to be a species of green algae in the genus Trebouxia. Trebouxia is the algal genus most commonly found in lichens, although rarely observed free-growing. Usnea is a commercially important genus of lichen due to its production of usnic acid, an effective antibiotic against at least 16 known strains of gram-positive bacteria, including Streptococcus and Staphylococcus (members of which are responsible for strep and staph infections, respectively). Usnic acid appears to disrupt the bacteria’s metabolic function, although it does not adversely affect human cells. Use of Usnea is not limited to homeopathy—many thousands of pounds of are harvested each year for used in antibiotic ointments and to control bacterial growth in cosmetics, such as deodorant.

This branch was found in the outside Clayton, and harbors at least two other types of lichen.

Hazel Galloway

Source:

- Brodo, Irwin M. Lichens of North America. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001.